[Archived from original facebook event page on 28 December 2021]

16 January 2019

It's that time of the year again.

What the art week represents now is a normalisation of production and consumption under capitalism. The fate of the contemporary art fairs shouldn't even matter to us. Let them come, let them fail. All we have to know is that any idea of art driven by excitement for grooming the collecting class serves only a select few. Yet the logic of the market goes well beyond the walls of warehoused gallery booths and the commodified luxury object. This is evident in the very origin of the art week, and the way vibrancy is forcefully created through funding a deluge of activities to appear at the same time. This is an image operation for tourists and traders, but a mere extension of treating artists as content creators. They tell us this is good for the industry, necessitating the hardening of professionalised hierarchies, as if this programme could get infinitely bigger, in denial that the competitive system of art being modelled after is designed to not accommodate everyone. We clamour for gigs, thankful with whatever we land, implicitly accepting that hype and exposure in a space of scarcity is still better than nothing at all. But that scarcity is symptomatic of something untenable, like the vast differences in wealth distribution and the possibilities for life we see foreclosed everywhere.

15 January 2019

Duration: 17 – 28 January 2019

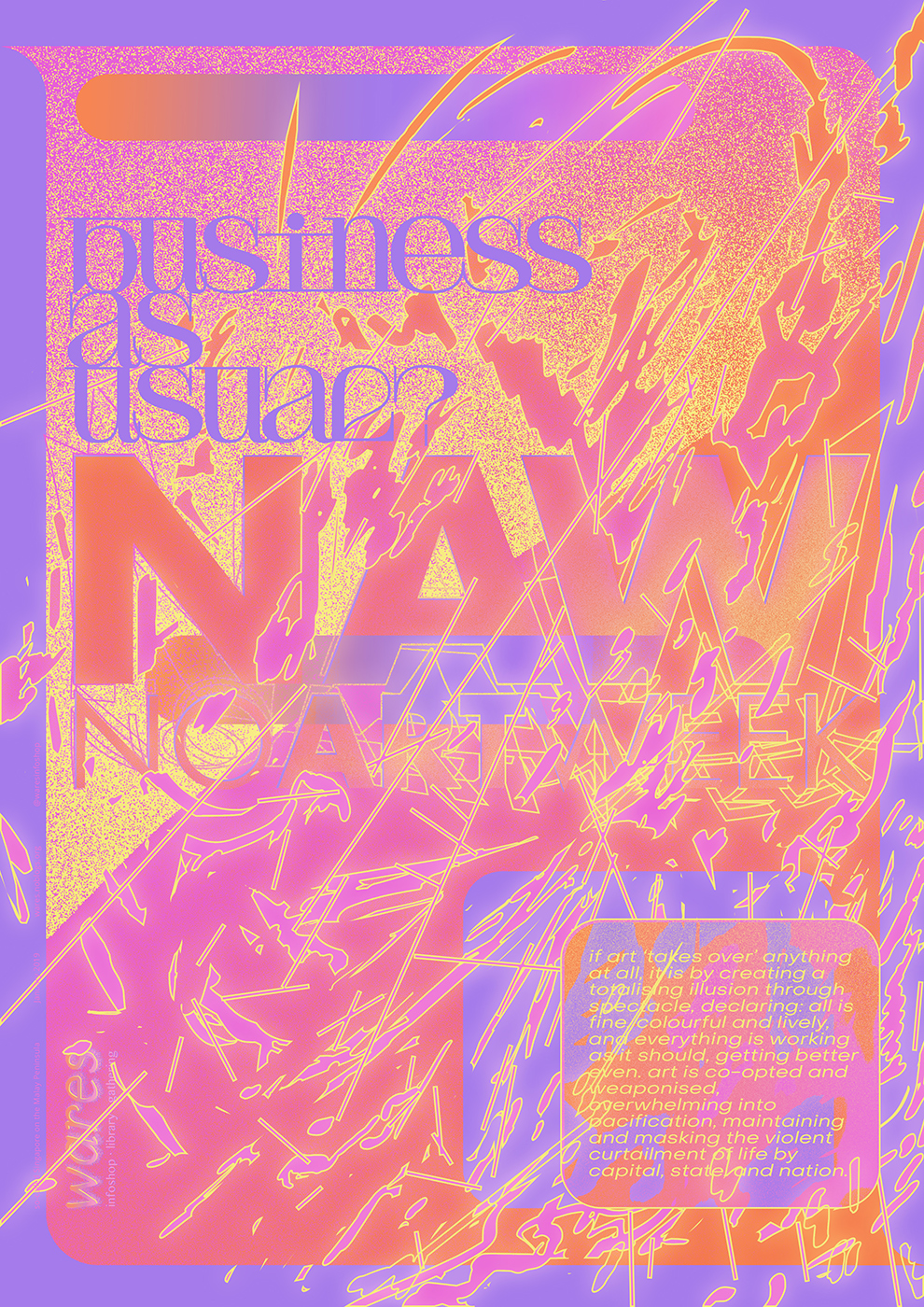

If art ‘takes over’ anything at all, it is by creating a totalising illusion through spectacle, declaring: all is fine, colourful and lively, and everything is working as it should, getting better even. Art is co-opted and weaponised, overwhelming into pacification, maintaining and masking the violent curtailment of life by capital, state, and nation.

After seven years, have we sunk into unquestioning all this as fact? What the art week represents now is a normalisation of production and consumption under capitalism. The fate of the contemporary art fairs shouldn't even matter to us. Let them come, let them fail. All we have to know is that any idea of art driven by excitement for grooming the collecting class serves only a select few. Yet the logic of the market goes well beyond the walls of warehoused gallery booths and the commodified luxury object. This is evident in the very origin of the art week, and the way vibrancy is forcefully created through funding a deluge of activities to appear at the same time. This is an image operation for tourists and traders, but a mere extension of treating artists as content creators. They tell us this is good for the industry, necessitating the hardening of professionalised hierarchies, as if this programme could get infinitely bigger, in denial that the competitive system of art being modelled after is designed to not accommodate everyone. We clamour for gigs, thankful with whatever we land, implicitly accepting that hype and exposure in a space of scarcity is still better than nothing at all. But that scarcity is symptomatic of something untenable, like the vast differences in wealth distribution and the possibilities for life we see foreclosed everywhere.

For the next two weeks, art is imaged flowing over the city, the art week's promotional material conveying a sense of the sticky and sickly sweet, something inescapable and lingering. In places, it takes the form of artwashing over racialised policing and ongoing gentrification, or elsewhere, celebrating in concert the truly disruptive colonialist architecture of accumulation. It is not that we are oblivious to all this, so many are already well tired of the assault or clued in to discourses developing globally, but here, we feel powerless to change anything, the only choice seeming to play along or fade into irrelevance. And to be sure, it isn't that art means nothing anymore, nor that in each encounter nobody could be moved by it, but neither is it going to save us, and any amount of criticality or intellectualising that doesn't work towards dismantling these relations would simply serve to reinforce them. The art institutions already play that game well, PR machines pretending that their hands aren't already similarly tied while churning out shows under the guise of challenging boundaries.

If art has its basis in imagination, let us imagine a life worth living.

This art week, say NAW. Not to disappear, but to negate. Actually take over. Meeting in or out of an event, start a conversation, between each other as co-workers, classmates, friends, strangers. Step outside of being artist, producer, curator, manager, art-lover; being bound by demarcated identities. Talk about what we are labouring for, how we work, what we think of as leisure and what we'd do, dreams of what we want art to be, in a world not ordered by wage, rent, and debt.

Interrogate class power, precarity, sustainability, and the systemic dispossessions imposed through gender, race, and ability. Detach from notions of necessity assigned to the state, the conflation of comfort with repression – imagine art-in-community created autonomously and not instrumentalised by authority; imagine being able to make, present, and discuss without the baggage of bureaucracy and gatekeeping; imagine the political not to mean their politics but what concerns our collective ability to live; imagine the ways to get there.

Build.

Begin forming out of these conversations overlapping circles of interdependent care and support, sharing space, resources, and skills. Withdraw from competing where you can, creating in ways that don't serve to accumulate value or deeper entrench current ways of doing things. Situate our creative actions close to life, tied to the immediate contexts of living or employment, discovering what solidarities with others could come into being, outside of naively thinking art alone makes lives better. Organise and get that bread together, for divestment from extraction, to destitute the present, towards a shared life in common.

This is not an event, we don't want to add to the mess with another thing to consume, another addition to the festival of aestheticised lifestyle options. We will be sharing texts and links through our infoshop and page, and we welcome you to do the same with us. If there's something you'd like to share, send it in, even if it is a thought, an idea, a call to meet. Our library of books, zines, and other printed matter remains open three times a week, so if you need room to rest, to breathe, to dwell, to find each other, we hope this space can do that for you.

19 January 2019

"Strike work feeds on exhaustion and tempo, on deadlines and curatorial bullshit, on small talk and fine print. It also thrives on accelerated exploitation. I’d guess that—apart from domestic and care work—art is the industry with the most unpaid labor around. It sustains itself on the time and energy of unpaid interns and self-exploiting actors on pretty much every level and in almost every function. Free labor and rampant exploitation are the invisible dark matter that keeps the cultural sector going.

Free-floating strike workers plus new (and old) elites and oligarchies equal the framework of the contemporary politics of art. While the latter manage the transition to post-democracy, the former image it. But what does this situation actually indicate? Nothing but the ways in which contemporary art is implicated in transforming global power patterns."

Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy, Hito Steyerl, in e-flux Journal #21, December 2010 [link]

22 January 2019

"Unfortunately artists make great capitalists, because they are skilled at generating new objects and sites of value. Urban capitalism assiduously seeks the new, because the old and existing have depreciated exchange value. Neighborhoods are profitable as they first rise, but to generate the same profits must be constantly remade – a process that means any place in the city becomes a frontier as soon as it is built. Real estate development’s drive to novelty and change mirrors that of art practice, and the need for the currency of new work to maintain stature through sales, publications and academic attention. Although artists often are drawn to cheap spaces because they lack affluence, their presence and practices handily serve revanchist capital. Both artists and developers like 'deals,' and both know that they have to produce 'new work' to generate exchange value (monetary or intellectually). The assertion of authenticity reifies exchange value.

(…)

Gentrification really is the way in which the urban geography of money disintegrates solidarity among people. The protests in Boyle Heights speak sentences in which the idea of the art gallery is actually the verb, not the subject. The subject is money. If artists there and elsewhere reject the protests, offer weak apologetics, or shy away from the delicate business of locating in neighborhoods where people are very different from the artists, gentrification won’t be sent into abeyance. Fundamentally artists have the chance to awake to their own roles in making the spaces of the city, and their own relationship to capitalism. The easy part of this is to see how artwashing and other uses of art serve power, but the hard part is examining what happens inside of the galleries and studios. Are those spaces inscribing social exclusion, or are they realizing openness and inclusion? While artists are great at producing individual works of value, they are even better at being agents for transmitting collective consciousness. Artists have the power not just to break down the physical barriers dividing the city, but also seeing and destroying the soft social walls. Art offers an escape from our tortured and divided urban geographies, because it can create new spaces that bring us together.

In fact, the Boyle Heights narrative repeated in articles is erroneous. Looking at the politics of the protestors, evinced in beautifully powerful events as well as banners and other visual devices – one should see them as artists in their own right, probing the imaginary to deliver a new Boyle Heights. The question for the galleries and studio artists is whether they will join in solidarity, or reinforce the lack of human intimacy that allows money to define social life in their neighborhood."

The Spaces of Gentrification, Michael R. Allen. 2016, in Temporary Art Review [link]

27 January 2019

"In general terms, the conflict has to do with art’s complicity in the process that we call gentrification – a term that gets thrown around a bit carelessly, it’s true. Often, saying 'gentrification' is a way to avoid saying 'capitalism.' Clowning white hipsters is cool (also – they aren’t always white, or hip), but it shouldn’t distract from the fact that the bigger enemy is the real estate industry, not to mention employers who don’t pay workers enough to make rent. Some extremely violent forms of gentrification won’t necessarily look like the stereotypical 'artists with fixies and cold brew moving into the hood' narrative. What if we talked about new Chinese money pushing out poorer people of Asian descent in the San Gabriel Valley at the same time as we talk about Boyle Heights, for example? In economic terms the phenomenon might not be that different. There’s a danger of reinforcing existing forms of oppression and exploitation in the name of a preexisting community that supposedly overrides class divisions. That said, gentrification often does look like artists with fixies and cold brew moving into the hood, which is why these events east of the LA River have a meaning that goes far beyond the local context.

What is important about the struggle in Boyle Heights, and what makes it different from any other anti-gentrification conflict I know of, is that it’s developed into a direct confrontation between the 'radical' art world and a local opposition that won’t back down, even when offered the chance for dialog. This is how you win. For example: a huge victory for the anti-gentrification campaign was the closure of the gallery PSSST in February of this year. Representatives of PSSST described their project as queer, feminist, politically engaged, and largely POC. All of which are perfectly good things in themselves, of course. A space for queer, feminist, politically engaged POC artists and their friends only becomes a problem when it contributes to a colonial, gentrifying dynamic. Which will inevitably happen as soon as well-connected art world people move into a historically working class neighborhood, regardless of their color or credentials.

This isn’t a matter of intentions or consciousness. No doubt PSSST thought they were doing good. It’s a matter of economics – in other words, stuff that happens whether you want it to or not, because there’s money to be made. Real estate developers don’t give a shit about your MFA in social practice art. PSSST never understood this. People in Boyle Heights did. PSSST was all about 'dialog.' So is every gentrifier. Refusing dialog was the best (in fact the only) strategic decision the neighborhood’s defenders could have made. There’s no such thing as dialog when one side is pushing you out of your home. The fact that groups like Defend Boyle Heights have been so willing to engage with their enemies is the shocking thing, not their supposedly aggressive tactics."

About Hating Art, Asmodeus. Included in ediciones inéditas anthology zine [link]